Long before the headlines about Cherokee DNA research began circulating, whispers of hidden histories had circulated quietly among scholars and community elders.

Some geneticists suspected that the story of America’s first peoples was far from simple—that beneath the familiar Bering Strait migration theory lay traces of movements, encounters, and connections that textbooks had overlooked.

Now, with advanced genomic technology, those subtle clues are beginning to surface, hinting at a history more tangled, mysterious, and far-reaching than anyone imagined. Could it be that the true story of human settlement in the Americas has been hiding in plain sight all along?

For centuries, history textbooks have presented a single narrative regarding the first inhabitants of North America: their ancestors crossed from Asia via the frozen Bering Strait thousands of years ago. This explanation, widely accepted by scholars and educators, has long formed the foundation for understanding how the Americas were first populated.

However, breakthroughs in genetic research and DNA analysis are revealing a far more intricate and nuanced story. Recent investigations into Cherokee DNA are uncovering evidence that suggests a richer tapestry of human migration—one that intertwines ancient travel routes, trade networks, and cultural exchanges spanning multiple continents.

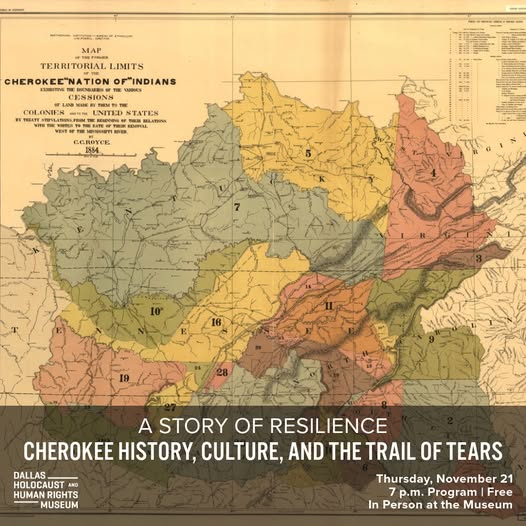

The Cherokee Nation, celebrated for its enduring cultural traditions and resilience, has long preserved oral histories about its origins and identity. Today, modern science is beginning to shed new light on those stories.

Through advanced genomic sequencing, researchers are examining ancient DNA markers—tiny fragments of genetic information that reveal patterns of ancestry and movement stretching back tens of thousands of years.

The studies confirm that most Indigenous peoples of the Americas share deep ancestral connections to populations in Northeast Asia, supporting the long-held belief that migration occurred via the Bering land bridge. Yet the research also reveals subtle genetic traces indicating multiple waves of migration—distinct groups of people arriving at different times and from varied regions. These successive movements have left behind a complex mosaic of ancestry, one that continues to shape Cherokee identity and cultural heritage today.

Conclusion:

The latest discoveries in Cherokee DNA are reshaping our understanding of the Americas’ earliest inhabitants, revealing a story that is far richer and more complex than the traditional narrative suggests. These findings highlight the interconnectedness of ancient populations, the multiple waves of migration, and the cultural exchanges that have left an enduring imprint on Indigenous identity.

By combining scientific evidence with the Cherokee Nation’s own oral histories, we gain a more holistic and nuanced perspective on the past—one that challenges simplified versions of history and underscores the resilience, diversity, and depth of the continent’s first peoples. This research is more than an academic revelation; it is a reminder that history is alive, evolving, and often more intricate than it appears on the page.